(AP): There were so many this year.

Sports in 2020 was an unending state of mourning. It was as if every week, sometimes days, another luminary fell, bringing a cascade of condolence and remembrance.

It began New Year’s Day, a harbinger of what the year held, with the deaths of David Stern and Don Larsen. Not long after came a seismic jolt, the helicopter crash of Kobe Bryant in the fog-shrouded California hills that reverberated across sports and across continents.

Deep into the year, a bookend to Bryant, Diego Maradona died from a heart attack in Argentina weeks after brain surgery, the waves of grief rippling across soccer. It seemed a whole wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame was ripped away — Al Kaline, Tom Seaver, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Whitey Ford, Joe Morgan, Phil Niekro. Football lost a big piece of its heart: Don Shula, Gale Sayers, Paul Hornung, Bobby Mitchell. Gone from college basketball was John Thompson, as imposing and important a coach as any.

The losses, of course, came against a backdrop of a pandemic, its number of fatalities rolled out daily on TV screens. Sports took its place in the grim procession, even if COVID-19 was not listed on the death certificate. For fans of a certain age, it was as if the lights dimmed on a generation of players who long illuminated the game.

What was left were snapshots and YouTube montages and endless conversations — the soaring move to the basket, the steely command on the mound, the slashing run past tacklers, the burst of an impossible goal. It’s all a fan could ask for.

Bryant was among nine who died that January day, including 13-year-old daughter Gianna. He was 41, less than four years removed from the NBA, and on his way to a youth tournament. Bryant is the game’s fourth-leading scorer. He spent 20 years with the Los Angeles Lakers, 18 as an All-Star, and won five titles. He was a generational player who left an imprint with his swoops and scores, his touch and grit. Purple and gold became colors of mourning. “It doesn’t make no sense,” the Lakers’ LeBron James said. “But the universe just puts things in your life.”

Maradona was the soul of Argentine soccer whose magic extended to Italy, where he bewitched Napoli fans. He carried Argentina to the 1986 World Cup title, his two goals in a quarterfinal against England among soccer’s greatest: the “Hand of God” goal — he later acknowledged it came with his hand, not head — and another in which he shredded an entire defense. He died at 60, his health undercut by cocaine and obesity. One commentator in Argentina likened him to the “great masters of music and painting.”

Kaline spent 22 years with the Detroit Tigers, elegantly covering right field and in 1955 hitting .340 at age 20 to become the youngest player to win the American League batting title. He was simply Mr. Tiger. In Cincinnati, Morgan, his elbow twitching at the plate like the wing of an agitated chicken, was a maestro at second base, a two-time MVP and vital part of the Big Red Machine before becoming a TV voice of the game.

Ford was the dependable “Chairman of the Board,” a left-hander who played on six title winners and might have been the greatest starting pitcher in New York Yankees history. In St. Louis, Gibson struck palpable fear into batters. He won seven straight World Series starts and in 1968 had a 1.12 ERA. Baseball responded by lowering the mound the next year. A month earlier, Cardinals fans also grieved for Brock, who came over from the Cubs and became one of the game’s great leadoff hitters and base stealers.

Three days earlier, it was Seaver. He was “Tom Terrific” and “The Franchise,” both nicknames apt. Seaver shook the mindset of the New York Mets. He was a three-time Cy Young Award winner and cornerstone of a team he transformed from woebegone to World Series champion in 1969. Niekro won 318 games and pitched until he was 48, his knuckleball dancing and mystifying batters across the decades.

Larsen was 81-91 over 14 big league seasons, but on one October day in 1956 the gods of the game visited an Everyman. The Yankees pitcher did what no one in baseball ever had — throw a perfect game in the World Series.

Baseball also remembered Dick Allen, a fearsome slugger and seven-time All-Star who withstood torrents of abuse in Philadelphia. Two other hard hitters left: Jim Wynn, the Astros’ “Toy Cannon,” and Bob Watson, who later with the Yankees became the first Black general manager to win a World Series.

Three Dodgers went in the space of a week — reliever Ron Perranoski and outfielders “Sweet” Lou Johnson and Jay Johnstone. A trio of second basemen — Glenn Beckert, Frank Bolling, Tony Taylor — died as did John McNamara, who in 1986 managed the Boston Red Sox to within one strike of a World Series crown. And Phil Linz, the light-hitting backup whose harmonica playing on the team bus became part of Yankees lore.

In basketball, Stern became NBA commissioner in 1984 and inherited a league in perilous financial shape. He sprung it to life, riding the star power of Magic Johnson, Larry Bird and Michael Jordan and reconfiguring the game for the global marketplace.

Thompson, a towel draped over his shoulder, guided Georgetown to the 1984 NCAA championship. He was the first Black coach to take the title. Thompson was outspoken and big — he could look at Patrick Ewing eye to eye — and fierce in defense of his players.

There was K.C. Jones, the guard who shut down the best of players and won eight straight titles with the Boston Celtics before coaching them to another two. Jones played on those Bill Russell teams with two Hall of Famers who died in 2020: Thompson and Tom Heinsohn, who would go on to coach and broadcast for the Celtics.

Gone, too, were Wes Unseld, with his whipping outlet passes, star sixth man Cliff Robinson, Harlem Globetrotter dribbling wizard Curly Neal and ex-ABA Commissioner Mike Storen. There was a roster of coaches in Jerry Sloan, Eddie Sutton, Lou Henson, Carl Tacy, Billy Tubbs and Morgan Wootten.

The NFL lost dazzling running backs in Sayers, Hornung and Mitchell.

Sayers played only seven seasons but his open field running with the Chicago Bears became the stuff of legend. His fame grew through “Brian’s Song,” a movie about friendship and a dying teammate.

Hornung, the “Golden Boy” and Notre Dame Heisman Trophy winner, helped forge the Green Bay Packers dynasty. He was suspended for a year in 1963 for gambling. Hornung enjoyed the good life, the counterpoint to the stern Vince Lombardi, and made no apologies for it.

Mitchell was tantalizingly fast. He split his career between Cleveland, where he teamed with Jim Brown, and Washington, where he became the team’s first Black player.

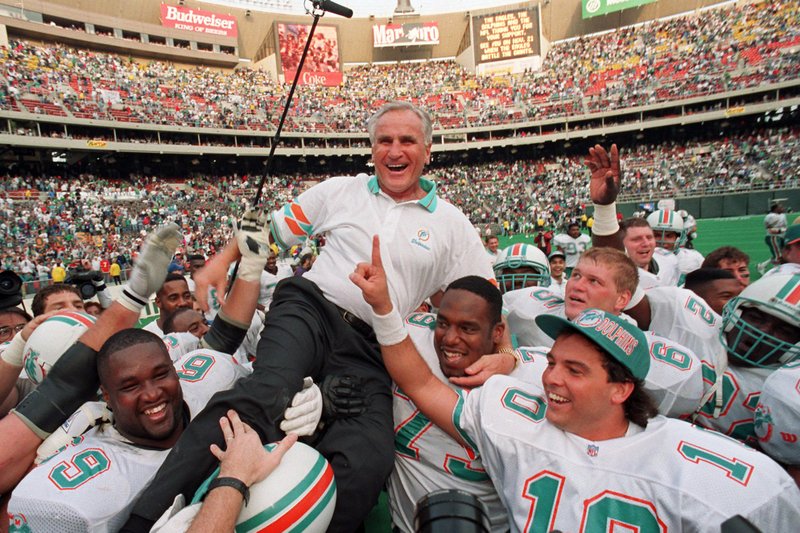

Shula once said that in judging greatness the stats should speak for themselves. Here are his: He guided the Miami Dolphins to the only perfect season in NFL history — 17-0 in 1972 — set a league record with 347 victories and coached in six Super Bowls. “If there were a Mount Rushmore for the NFL,” Dolphins owner Stephen Ross said, “Don Shula certainly would be chiseled into the granite.”

The Packers also mourned defensive greats Herb Adderley, Willie Wood and Willie Davis while the Dolphins did likewise with running back Jim Kiick. Two linebackers were remembered: Mike Curtis, who helped the Colts win a Super Bowl, and Kevin Greene, his long blond hair flowing while in manic pursuit of quarterbacks. Tom Dempsey, born without toes on his kicking foot, made a then-record 63-yard field goal. His was among the COVID-19 deaths. Among the coaches lost: Joe Bugel, Pat Dye, Johnny Majors, Ray Perkins, George Perles, Pepper Rodgers, Harland Svare, Sam Wyche.

Hockey sent off Henri Richard, the diminutive center who won a record 11 Stanley Cups with the Montreal Canadiens. He was the “Pocket Rocket” and younger brother of superstar Maurice “Rocket” Richard. There was also Eddie Shack, the always entertaining winner of four Stanley Cups with the Toronto Maple Leafs; and Dale Hawerchuk, who spent 16 years in the NHL, notably with the Winnipeg Jets.

The Olympic flame flickered for Rafer Johnson. He won a gold medal at the 1960 Rome Games in the decathlon, an event that commanded far more prestige then than today. Eight years later he helped subdue Robert F. Kennedy’s assassin. Kurt Thomas in 1978 became the first U.S. male gymnast to win a world title but lost an Olympic shot in 1980 because of the boycott.

There were farewells in golf for Mickey Wright, who won 13 majors and gave the early LPGA a big lift; and resplendently dressed Doug Sanders, who won 20 times on the tour but never a major.

In auto racing: Stirling Moss, the adventuresome British Formula One driver; versatile driver John Andretti of the famed racing family; and Vicki Wood, a pioneering NASCAR racer who died at 101.

Also making it to 100 was Robert Ryland, the first Black professional tennis player and later coach to Arthur Ashe and Serena and Venus Williams. In addition, Alex Olmedo, winner in 1959 of the Wimbledon and Australian championships; and five-time Grand Slam doubles champ Dennis Ralston.

In soccer, some World Cup champions: Jack Charlton, with England in 1966; Paolo Rossi with Italy in 1982. Boxing paid tribute to British middleweight champion Alan Minter and Roger Mayweather, a world champ who trained nephew Floyd Mayweather Jr.

In the broadcast studio, there was Phyllis George. She put aside her Miss America tiara to become a sportscaster, opening doors for women with her work on CBS’s “The NFL Today.” There was also Roger Kahn, the author who lyrically captured the Brooklyn Dodgers in “The Boys of Summer,” his death coming in a year in which it seemed winter was the only season.